As a flotilla of naval vessels from around the world participates in the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC) to sustain relationships in the maritime community, a century ago this week international navies converged for a remarkably different occasion—to drink the last of the U.S. Navy’s supply of alcohol. On July 1, 1914 the ships of the U.S. Navy officially became dry under General Order No. 99. “The use or introduction for drinking purposes of alcoholic liquors on board any naval vessel, or within any navy yard or station, is strictly prohibited, and commanding officers will be held directly responsible for the enforcement of this order,” reads the hundred year-old order. Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels issued the order. A teetotaler, former newspaper publisher, and supporter of the temperance movement, the North Carolinian had already become unpopular with many of those in the sea services. When the order was first announced in on April 16, 1914, it was met with derision and mockery in the press, which regarded the policy as an attempt to make the Navy softer.

Editorial cartoons dubbed Daniels “Sir Josephus, Admiral of the USS Grapejuice Pinafore” who oversaw a fleet of Navy ships with names such as “USS Piffle” that were bedecked with flowers, rocking chairs and potted plants. But Daniels’ order was actually just the final phase of a long process that had been slowly reducing the presence of alcohol on Navy ships.

Made in England

Inheriting Britain’s Royal Navy tradition of providing sailors with a daily ration of rum in the 18th century, the U.S. Navy established in 1794 that sailors were to receive “one half-pint of distilled spirits” a day. In 1806, the Navy encouraged the sailors to accept whiskey as a substitute for the more expensive rum. Sailors who did not wish to imbibe or were under age were paid an extra three to six cents a day. The ration was reduced to one gill (four ounces) in 1842 and totally eliminated 1862 during the Civil War—though the Confederate Navy continued to provide crews with rum rations, believing that the tradition would help recruit much-needed experienced sailors from other nations.

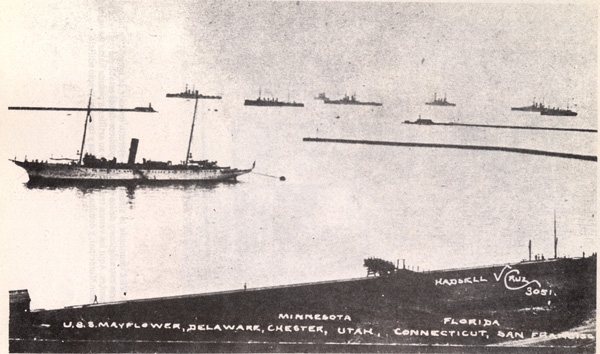

U.S. Navy sailors were allowed to keep their own stock of beers and undistilled spirits at the discretion of their commander until 1899, when even the sale of alcohol was banned to “enlisted men, either on board ship, or within the limits of navy yards, naval stations, or marine barracks, except in the medical department.” By the time General Order No. 99 was announced, the only alcohol left in U.S. Navy ships was reserved for the wardroom and the captain’s wine messes. As the deadline approached, many of the ships of the Atlantic Fleet were in Mexican ports, part of the occupation of Veracruz.

The Last Feast

The order had not been well received by the force. Mere mention of Daniels’ name elicited jeers and curses. Inspired by the editorial cartoons that had ridiculed the initial announcement, sailors had renamed a captured Mexican ship USS Piffle until it was spotted by an admiral, who smiled but demanded that it be repainted immediately. Commanders rushed to comply with the order by selling as much alcohol as they could but found that their stores still contained a sizable supply of booze in the days prior to the “bone-dry” date. It was decided that ships would host one last banquet to say farewell and consume the remainder of alcohol.

Some ships were content with piling tables with food and booze, others got more creative and created themes such as “Wild West” saloons or held funerals where mourners could watch John Barlycorn’s burial at sea. A few ships decided it was easier just to pour all the alcohol on board into one large bowl to make a very strong punch. With ships from several other nations in the region to observe the situation in Veracruz, the U.S. Navy invited foreign contingents to join in the festivities. Soon parties from the British, French, German, Spanish and Dutch navies began to travel by small launches from ship to ship to help eliminate the soon-to-be contraband. The occasion would also be one of the last peaceful interactions between the navies for many years. A world war would erupt by the end of the month; less than a year after participating in the event, the German cruiser Dresden was hunted down and knocked out of action by the Royal Navy.

Drinking Slang from the Navy

Groggy

– Grog is a concoction of rum, water and citrus juice that was originally drunk by British sailors and adopted by the U.S. Navy as a way to make stagnant water more palatable and to fight scurvy. Someone who is dazed or sleepy might feel as if they have had too much grog, making them “groggy.”

Three sheets to the wind

– Sheets on a ship are the ropes that control the sails. If a sheet becomes loose and starts flapping in the wind, the ship will lurch and rock. Someone who is cannot walk a straight line because they are staggering drunk is said to be “three sheets to the wind.”

Splice the main brace

– The main brace was the largest of the rigging on the ship and essential to controlling the vessel. A damaged main brace was difficult to repair, particularly in the midst of battle, so it became customary for the crew members who successfully spliced it to be rewarded with an extra ration of rum. The phrase came to mean a celebratory drink.

Binge

– To binge while on a ship meant to soak and rinse an empty cask in water. Sailors who needed more alcohol than their allotted ration would drink the binge water from rum casks in hopes that it would contain at least a few drops of booze. Binging also caused the wood to absorb water, much like a person binge drinking in the modern sense absorbs alcohol.

Down the hatch

– When sailors threw their heads back and poured alcohol down their throats, they equated it to manner in which cargo was loaded on ships by lowering it through the hatches on the deck.

Mind your Ps and Qs

– Popular folklore states the phrase refers to barkeeps having to be sure to track the “pints” and “quarts” ordered by sailors, but it more likely stems from the printing industry’s need to avoid accidentally reversing the letter blocks for “p” and “q” on the press.

Cup of Joe

– The common story that the term “cup of joe” for coffee originated from Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels’ order to prohibit alcohol in the fleet is probably a myth. The more plausible theory is that “joe” derives from “jamoke” – another nickname that was formed by combining the names of the coffee producing locations of Java and Mocha.

U.S. ships around the world held similar events to rid themselves of alcohol and mark the end of an era, but none came close in size and international participation than the soiree off Veracruz. When the 21st Amendment was ratified in 1933, the Navy conducted an informal poll of flag officers to determine if the policy of keeping the Fleet alcohol free should be reconsidered. The results of the poll clearly indicated that Navy leaders strongly preferred to continue prohibition on the ships, though the policy was modified to allow alcohol on shore at stores and clubs.

Exceptions

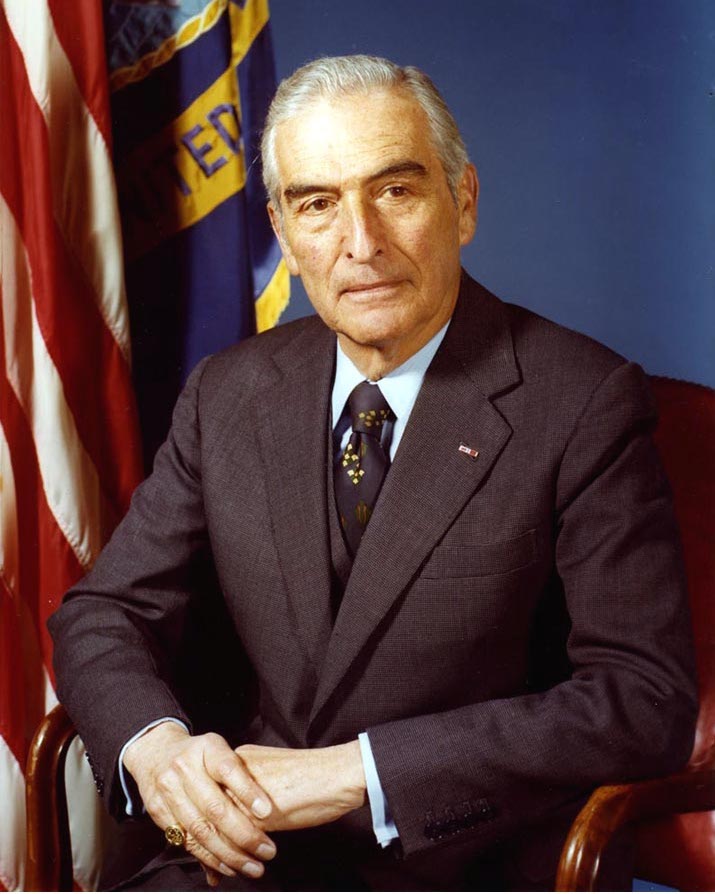

There are exceptions to the rule. Ships keep a small stock of alcohol for so-called medicinal purposes such as when a crewmember is shaken by an accident or a pilot is suffering from the pressures of a demanding mission. The alcohol can only be issued on the authority of the medicinal officer or captain of the ship. During World War II, some submarine commanders, such as Adm. Eugene Fluckey of the USS Barb tried to relieve the stress of living in a contained and dangerous environment by providing his crew with beer after an enemy ship was sunk. In 1980, Secretary of the Navy Edward Hidalgo decided to allow crew members of ships that had been out to sea for an extended period to each have two beers (later set to 45 continuous days). According to letter by Capt. Lawrence B. Brennan, published in Naval History magazine, the surprise announcement to again permit limited beer on board was prompted by Hidalgo’s experience on USS Enterprise during World War II when a kamikaze attack plane crashed though an elevator and destroyed the cargo of beer.