This is the first of two articles on the current crisis in Ukraine and on the history of conflict in the region. The second will outline possible policy options for the international community.

The events of the last three weeks have catapulted Ukraine to the forefront of the U.S. policy agenda, sparking an intense crisis of confidence between the United States and Russia—the worst since 1979.

Russia is stridently claiming that Crimea should have a “right of return” to Russia, and the United States is citing concerns about territorial integrity and the sovereignty of state borders.

Europe and the United States are almost certainly not willing to go to war over Crimea—and Russia almost certainly is.

Unlike the Cold War, this is not a simple U.S.—Russian issue. Rather, U.S. and Russian interests both converge and collide over issues ranging from space, the Arctic, the Pacific, Iran, and energy security in myriad ways and places.

What brought this issue to this crossroads, and what are the implications for the immediate future as well as the long term?

The history of Russia, Ukraine and Crimea is complex; even more complex is the role of democracy in the so-called “Borscht Belt” and the ability of civil society to create an enduring, sustainable local-flavored democracy that allows a nation of almost 50 million, seated at the crossroads of Central Asia, Russia, Europe and the Black Sea, to find its own autonomous way forward in a complex neighborhood.

It is a complexity built on centuries of common culture and shared history, as well as unique regional traits. Regrettably, neither the United States. nor Europe have time to take a crash course in East European history—but their consideration of options must be grounded in a realistic appreciation of the facts and levers as they are, not as we might wish them to be.

‘I Live in the East — Not the West’

In order to best understand the past fifteen years of Russian history, and how Russian President Vladamir Putin has arrived at where he is in this crisis, one must first understand how Putin views Russia, his immediate neighbors, Russia’s national interests and the rest of the world.

“I live in the East, not the West,” he said in 1999.

Putin appears to have played the last decade well by identifying national goals and policy priorities, and putting into action activities to support and achieve his aims.

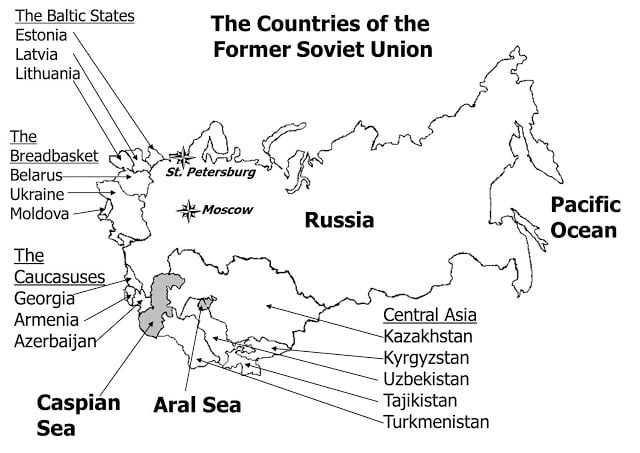

To that end, the crux of the issue in current Crimean standoff is Ukraine desires to be free and clear of the former Soviet Union, while Russia wants to readdress the dissolution of the Soviet Union and re-litigate borders that have been in flux for centuries.

To illustrate the dynamics, we need a quick canter through history.

Shifting Control

It has been a very long time (at least three centuries) since Ukraine has been effectively ruled as an independent and sovereign state.

It has been a very long time (at least three centuries) since Ukraine has been effectively ruled as an independent and sovereign state.

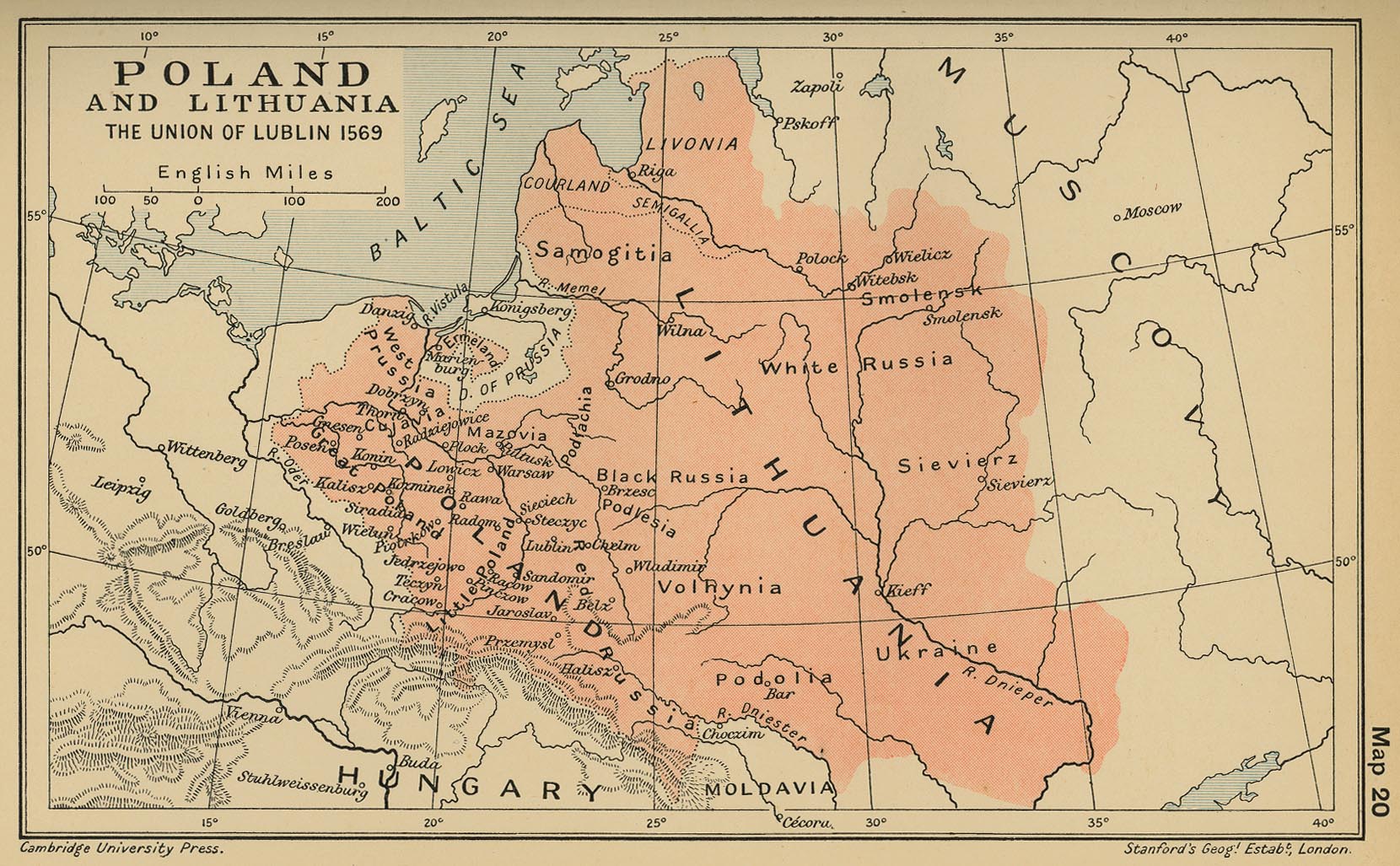

The region was part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth under Polish rule beginning in the mid-1500s.

Poles occupied Moscow during part of the Russian Time of Troubles (smuta in Russian, which in Polish ironically means “sadness”) in the early 17th century, even as Cossacks rampaged across Ukraine (the kresy in Polish) and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth struggled to maintain its super-power status.

Then a distracted Europe enabled confusion and chaos in Ukraine.

The Cossack uprising of the Khmelnitsky’s Rebellion shattered Polish governance (1648-1657), as Western Europe was signing the Westphalia Treaty and recovering from the twin ravages of the Plague and the Thirty Years’ War.

Austria was part of the three-nation dismemberment of Poland in the late 18th century, and as a result gained Galicja, a region that encompassed most of today’s Ukraine west of Kiev.

Soviet Influences

The period after World War I saw Czarist Russia collapse, and then a series of brutal civil wars, as well as a war with Poland (the Poles won, much to the chagrin of a young komisar named Joseph Stalin), meant that a Ukraine in the Soviet Union was not master of its own destiny.

The wheat fields of Ukraine were too valuable to the Soviet Union to be allowed out of their geopolitical orbit.

With the collectivization campaign, vigorously resisted, the farmers and peoples of Ukraine were brought to heel.

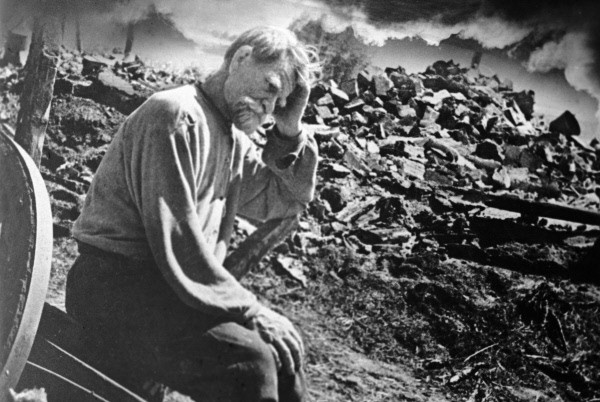

This was continued with two famines and the counter-kulak campaign that resulted in the chłodomor or Голодомор (in Ukrainian, the “Hunger-extermination”), the serial starving of Ukraine by the Soviets. Estimates range from 2.5 to 7.5 million killed—the mention brings shudders to Ukrainians.

This was continued with two famines and the counter-kulak campaign that resulted in the chłodomor or Голодомор (in Ukrainian, the “Hunger-extermination”), the serial starving of Ukraine by the Soviets. Estimates range from 2.5 to 7.5 million killed—the mention brings shudders to Ukrainians.

During World War II, Ukraine was a bitterly contested sub-theater of operations. Some Ukrainians fought for the Germans, others for the Soviets, still others (especially in western portions) for their own independence.

Accurate statistics are difficult to come by, but Ukraine along with Poland and Germany certainly saw a greater percentage of death and destruction than any other region in the war.

Stalin was replaced by Nikita Khrushchev, who was born in a small village close by the Ukrainian border, and cut his teeth as a young apparatchnik in Ukraine.

He was party to the crimes and policies of Stalin, yet during World War II he tried — with limited effect—to alleviate some of Ukraine’s suffering.

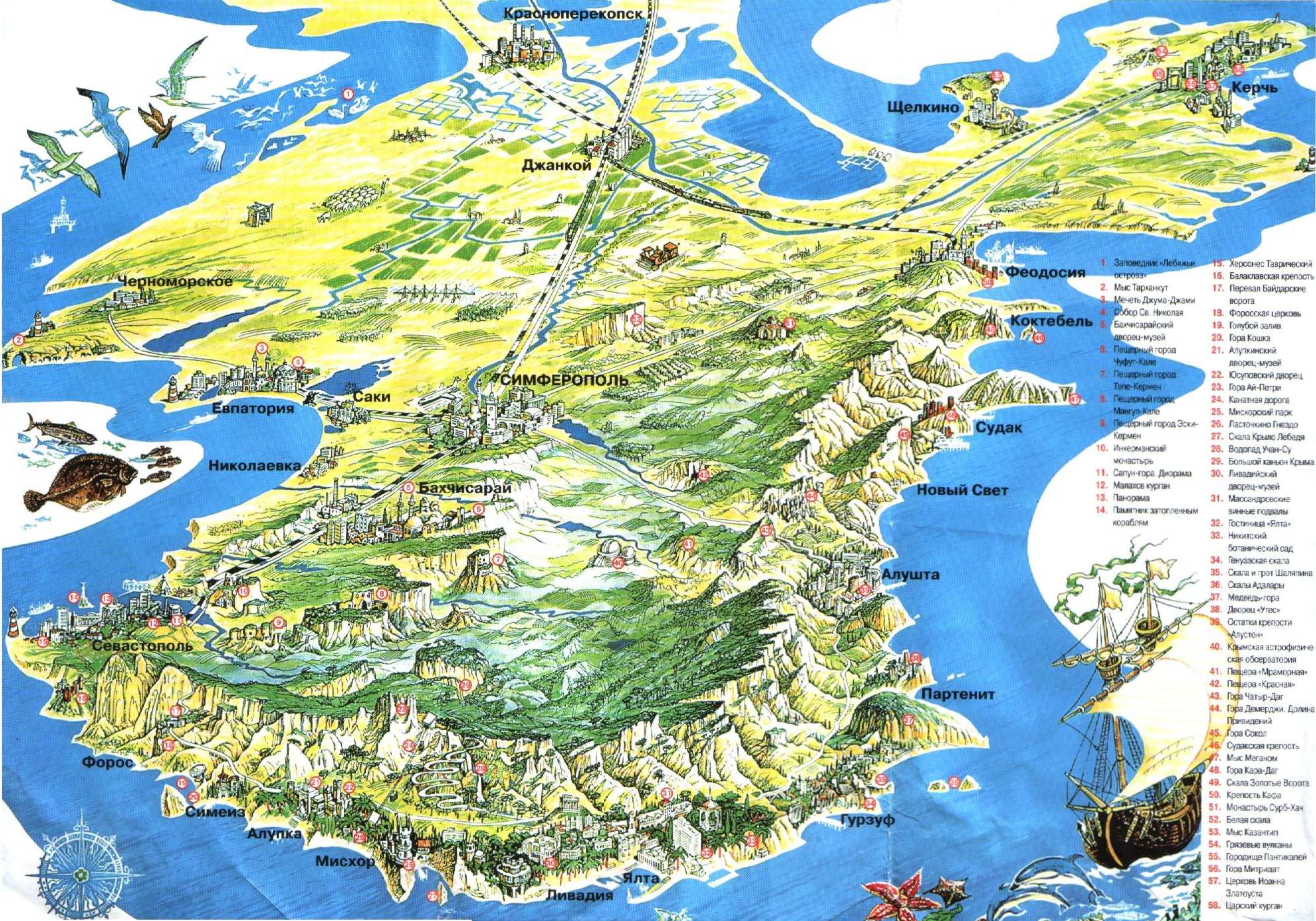

For myriad reasons, the USSR “gave” Crimea to Ukraine in 1950s in the immediate aftermath of the “Secret Speech” denouncing the legacy of Stalin and Khrushchev’s bungling attempts to reverse decades of deleterious Soviet policy.

Khrushchev, though, never anticipated that the USSR would dissolve, and that one day Ukraine would no longer be a satellite but a free and sovereign nation.

Today a central flashpoint is not “just” Crimea, but the entire complex post-USSR period in grappling with the fallout of two Russian empires collapsing in 75 years. One cannot understand Ukraine and Crimea without considering this pivotal period in Russian (Soviet)-Ukrainian relations.

Post-Soviet Period

On Christmas Day 1991 Mikhail Gorbachev resigned, stating that the, “disintegration of the Soviet Union had been a most tragic event.” By January 1992, Ukraine and 14 other former Soviet Republics had become independent nations.

On Christmas Day 1991 Mikhail Gorbachev resigned, stating that the, “disintegration of the Soviet Union had been a most tragic event.” By January 1992, Ukraine and 14 other former Soviet Republics had become independent nations.

Ukraine handed over all of its nuclear weapons, leading to the signing of the Budapest Memorandum of “Assurances” (a complicated term and document in international law and diplomacy) in 1994.

The people of Ukraine were rewarded with the poisoned candidate Viktor Yushchenko becoming president—Viktor Yanukovych was out, and a dynamic new prime minister, Yulia Tymoshenko, in as well in a fledgling coalition government.

This quickly changed in 2006, though, as Yanukovych staged a comeback and replaced Timoshenko as prime minister through 2007.

Ukraine, still grappling with emergent democracy as practiced, not as preached in western capitals far removed from Russia’s near-abroad, continued looking for a shared cultural and political understanding that could effectively lead the diverse peoples of Ukraine.

That experiment continues today with the demonstrations in Maidan and the political fallout.

Yanukovych tried to straddle a delicate balance between Russia and Europe. After NATO announced at the Bucharest Summit in 2008 that they would not offer membership to Ukraine or Georgia, relations between “Europe,” Russia, Ukraine and the United States seemed to improve, allowing the new president to announce a “reset” with Russia.

Events proved that perhaps this was overly optimistic as Russia (albeit provoked, a favorite Russian tactic) invaded Georgia in 2008, and in 2009-10 successfully pressured Ukraine to cancel military exercise with the United States and other NATO countries.

At the same time, Ukraine did deploy forces to Iraq early on, and while this may have endeared them to the United States and NATO, it certainly did not endear them to Putin’s Russia.

Yanukovych tried to work an agreement with the EU, but at the same time the Ukrainian treasury was empty (in part perhaps because he is alleged to have stashed billions of dollars skimmed form the till overseas).

When Yanukovych made a sudden about face from Europe and toward the deep pockets of Moscow, protestors took to the square.

According to most accounts, the protests had almost petered out, until the government sent in heavily armed forces to clear the square, and in the days of Instagram and other streaming social media, the strategic situation changed overnight, whilst simultaneously tremendously raising the stakes.

What Crimea Means to Russia

In Moscow there remains deep resentment at how the post-1991 borders were drawn, and perhaps nowhere is it more contentious than Crimea.

While most Russians have historically considered Ukraine an integral part of Russia (Solzhenitsyn, Tolstoy, et al), and Kievan Rus the birthplace of modern Russia, they are even more attached to Crimea.

Crimea occupies an emotional place in the heart of many Russians. They fought The Crimean War here in 1853-1856, disastrously executed by Prince Menshikov, embarrassing Russia across all of Europe, allowing the Ottoman Empire to totter on and the Austro-Hungarian Empire to extend and exert even greater control in the Black Sea region.

Russians resent their loss of prestige and power, and Crimea may well be the diamond in the Fabergé egg to them. It should surprise no one that a re-emergent Russia would seek to “correct” perceived borders, but, if Crimea today, does that mean Narva, Estonia tomorrow (with an ethnically approximately 90 percent Russian population)?

The question, then and now, boils down to what degree of Russian interference was/is Ukraine and the West willing to tolerate?

What’s Happening Now

Ukraine, like many former Soviet Republics, is a “Fourth World” country in that it must first dismantle the damage done by Soviet rule—the destruction of trust, consensus and civil society, as well as crumbling infrastructure—before it can rebuild.

Poland and others have done this, but not without significant struggle and assistance. The question is posed, then: Can Ukraine do the same and how much external assistance and assurance does it need?

In the 2000s, I once sat in a high level U.S. diplomatic discussion about Russia conducting its annual energy slowdown offensive to squeeze Ukraine, Poland, and most of Europe with restricted energy supplies and sudden price spikes. A very senior U.S. leader commented that “Russia hasn’t learned its lesson about doing this” and sage heads nodded obsequious concurrence around the table—except for me. I opined that in fact the Russians had learned their lessons—they could energy squeeze Ukraine, Poland, and Europe any time they wanted to and there was nothing that Europe or the United States could or would do about it.

Nonetheless, only having one spigot to turn limited the strategic choices of Russia and Putin, who wanted more nuanced options.

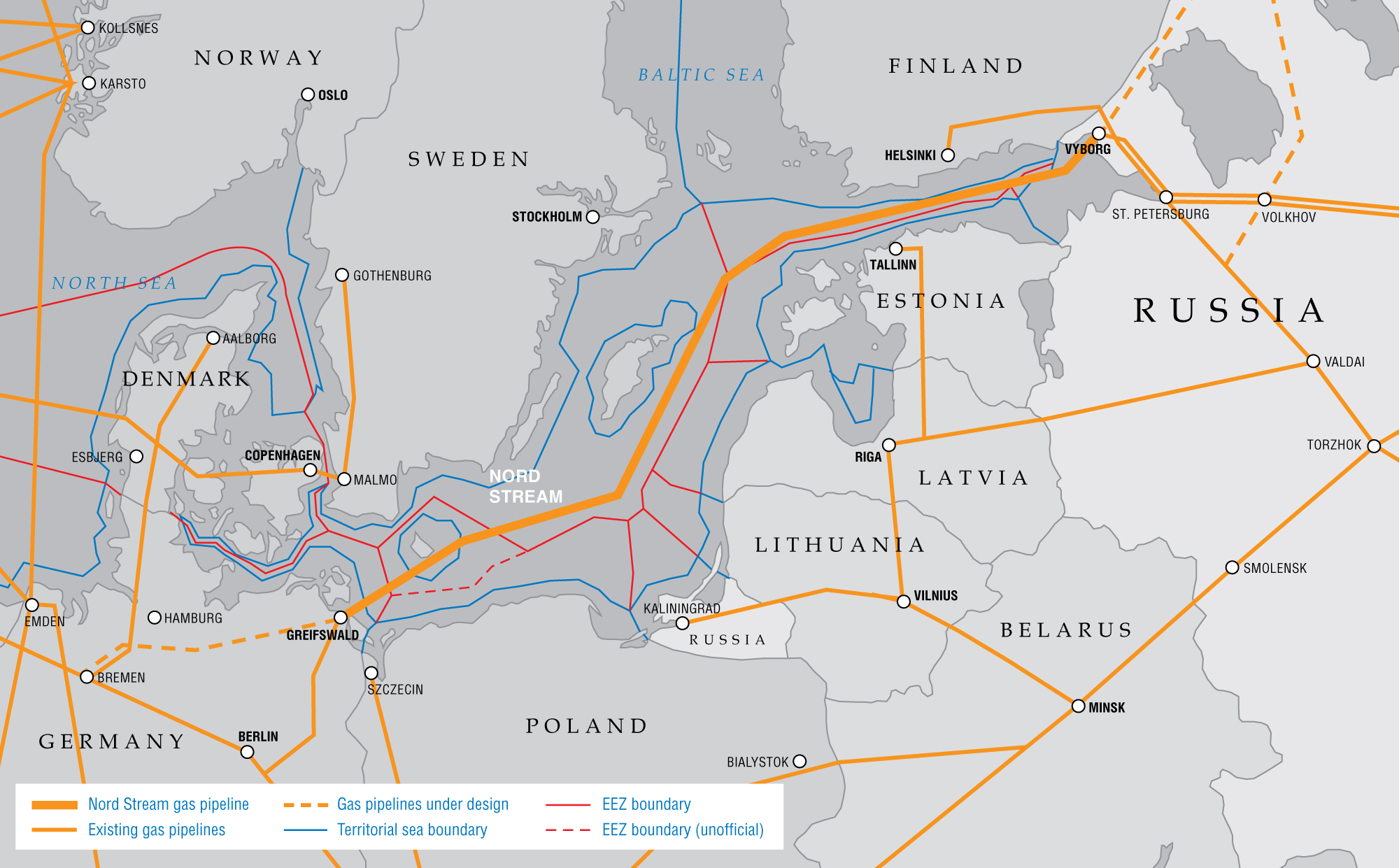

Three new energy pipeline projects allow Russia to have a symphony of energy options with which to optimize their regional power policies—Blue Stream, South Stream and Nord Stream.

It is worth noting that the original EU idea was built on coal and steel—because damp and frigid European winters demand a reliable source of energy with which to heat homes, businesses, and public buildings. With the extensive Soviet-era energy lines supplemented by these new projects, Russia now has the ability to increase energy supplies (and lower prices) to some parts of Europe whilst simultaneously constricting supplies (and raising prices) to other parts of Europe.

Using the energy weapon, Russia may be more powerful in Europe than at any time in the past two centuries—since Russian troops walked down the Champs Elysees yelling ‘bistro, bistro’ (quickly, quickly) to startled French waitresses—and without a shot fired or battalion mobilized.

Thus where we are this month with the Ukrainian-Russo crisis.

Only after we carefully consider the myriad factors at play in Ukraine we begin to carefully—albeit very quickly—begin crafting a “return to Europe” strategy that will provide the best set of compromise positions, policy and strategy to de-escalate this crisis, recognizing Russia’s interests while supporting the earnest yearnings of Ukraine to breathe free as a vast land of undulating fields and varied peoples at the crossroads of geography and history.